It's ok to lie about your game.

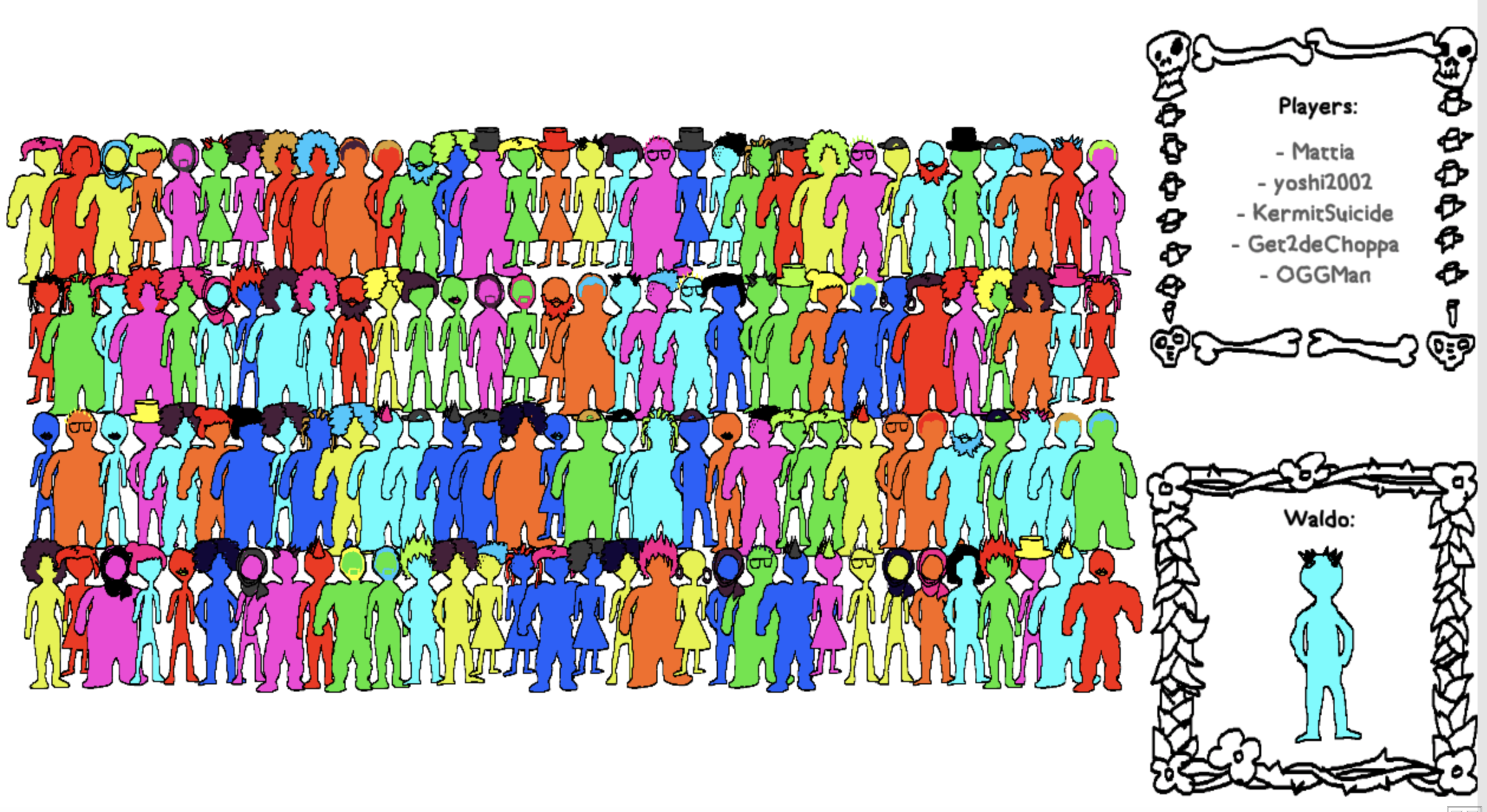

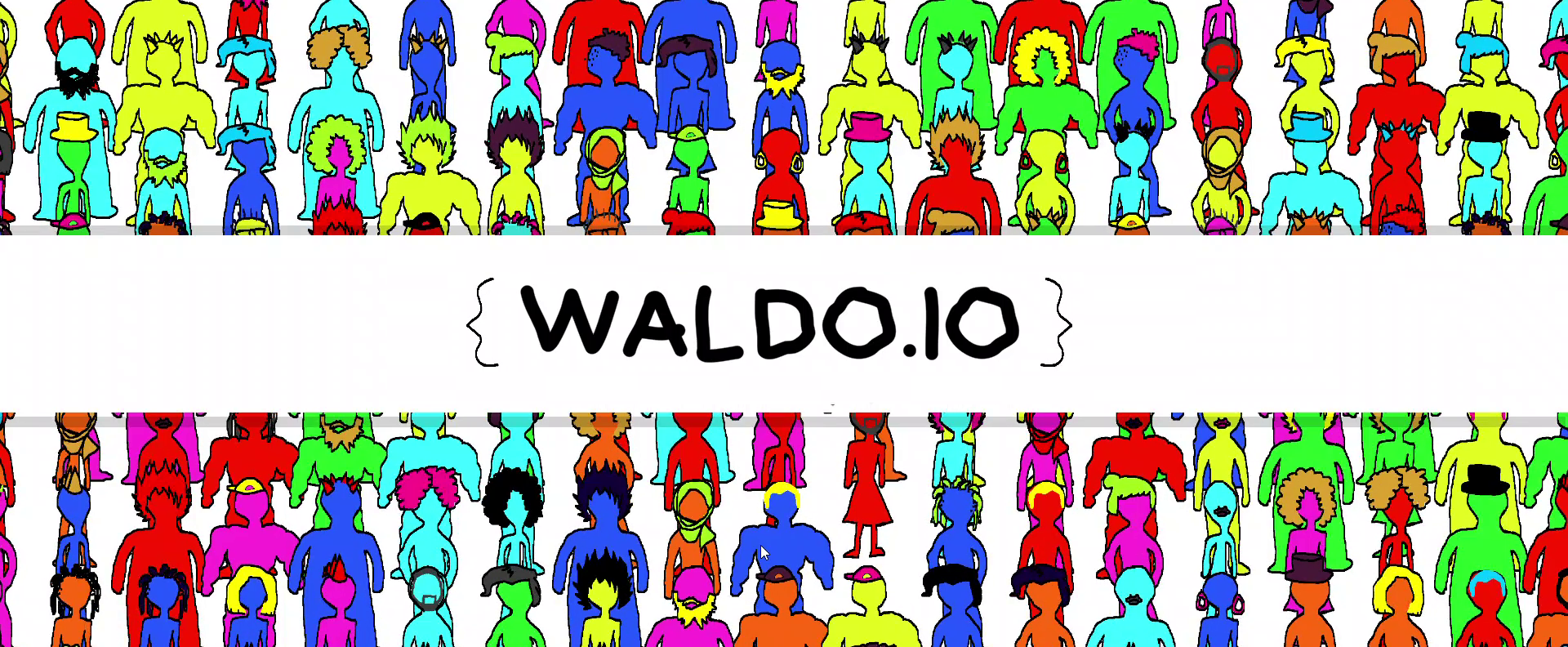

For the 2019 GMTK jam we decided to make multiplayer Where's Waldo for five players.

We are very proud of it: the game is simple, fun and possibly the most colourful thing we have ever made.

Except... it's not actually multiplayer.

When you first play the game, you might be forgiven for thinking that you are playing against other players. There's a fake lobby, and the game even generates usernames for everyone but you. We even went out of our way to make sure you can't play without an internet connection.

And you know what? The multiplayer feels real.

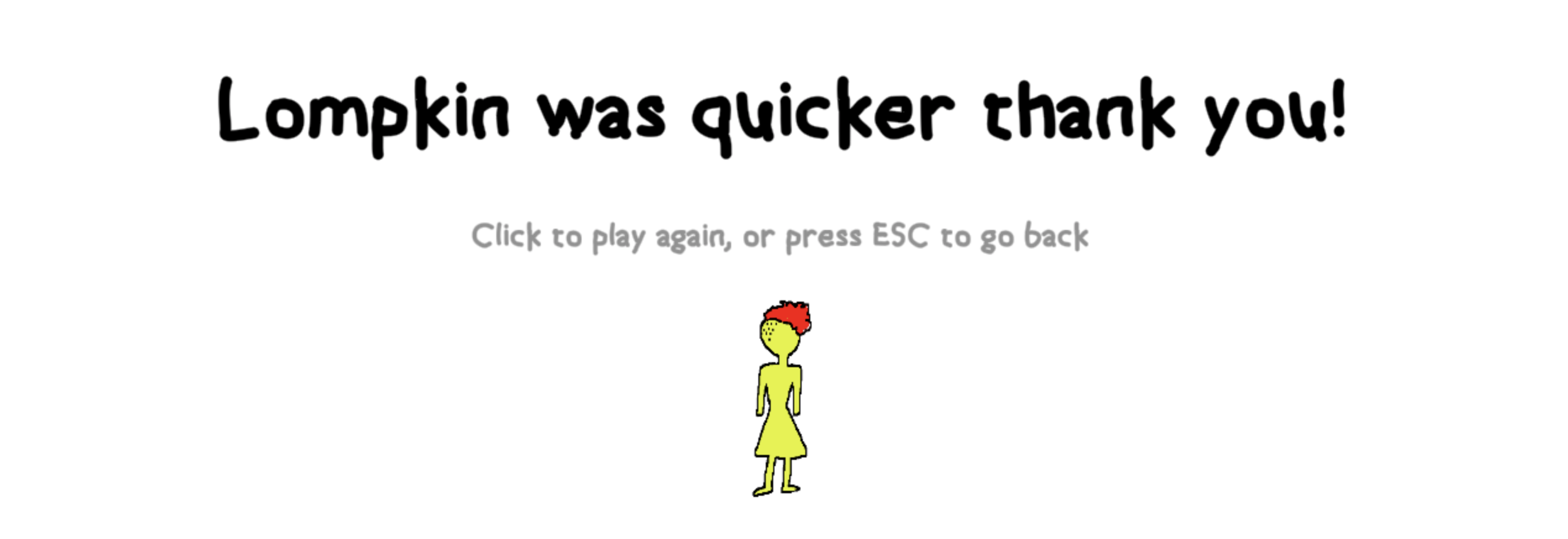

The "other players" are allowed to win, and sometimes they do.

The incredible thing that we stumbled upon is that knowing that the game was multiplayer was enough for most people to feel like it was.

The thrill of competition arose from just thinking that you were competing, and made winning feel great.

How incredible is that?

We even had people at our day job thinking they were competing against their colleagues because they thought they spotted their username in the lobby!

The hilarious reality is that the game doesn't even have a simple AI, it just starts a game-over timer and if you haven't won by then it just picks someone else as the winner.

This was our twist for the theme 'Only One': you think you're playing with others, but really it's just you.

To our surprise, the great majority of the players who liked the game before knowing it was solo, were delighted to realise it wasn't.

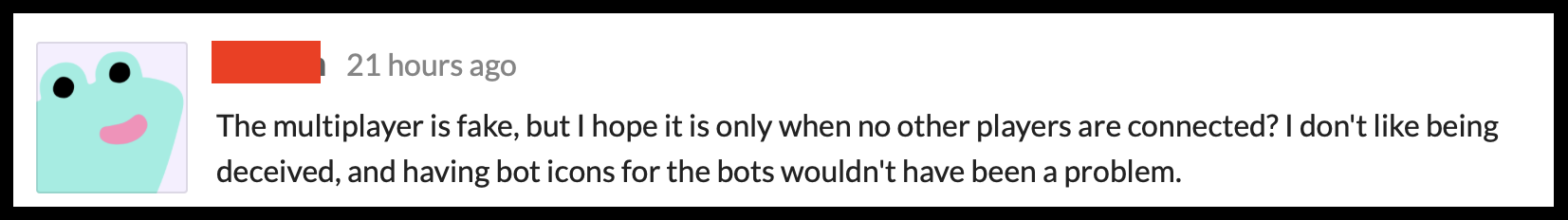

But not everyone.

We had been open about the nature of the game on the forums and Discord, but we never specified it on the game's description.

And why would we? The game works as an experiment because it initially deceives you!

GMTK is not a competition with a prize so we felt it was a very harmless joke. There's no commercial nature to waldo.io, but it does ask some fundamental questions about our relationship to video games.

If an experience works because of its deceptive nature, then how can a creator reconciliate that with writing a Steam description?

If a game is based on the element of surprise, then how can we bullet point the game's features on its cover?

In an age where creators are often criticised for misleading customers, how can such games exist if they get criticised even for a game jam?

There's two things I have learned from this game.

The first one is that emotions are a byproduct of your product and the context it exists in, with the context being perhaps even more important than the game itself. If you think it is multiplayer, it might as well be.

The second is that a large set of our consumers think that a game is a product that caters to their needs, instead of an experience. A game to them is akin to a car: you must know exactly which features it has, and exactly how it works.

These people aren't looking at a game. They are looking at a graph. And you know what?

Fuck graphs.

Let games surprise you.

Let games be experiences.

Let games lie to you.

Files

Get Waldo.io

Waldo.io

Compete against strangers to find the hidden Waldo!

| Status | Released |

| Author | Big Breakfast Collective |

| Genre | Survival |

Comments

Log in with itch.io to leave a comment.

Really interesting experience you created there. I think your point is very true. Emotions are a byproduct of a game and essentially the only thing that really matters. If by deceiving a player you can create an awesome experience, it's really not a problem in my opinion.

As you said, the main concern is for paid games where a consumer might feel annoyed and regret buying the game. However, I think all games deceive players to some extent. For example, the story can have a plot twist at the end of the game which is similar to deceiving the player until the very end.

Anyway, thank you for the interesting read!